The Beginnings of the Israel Exploration Society and Its Activity vis-à-vis the Mandatory Department of Antiquities

Ronny Reich

The Israel Exploration Society was founded twice. The first time was on 6 April 1913. In his article in the Hapoʿel Hatsaʿir newspaper dated 22 March 2013, Dr. A.B. Rosenstein proclaimed the foundation of the Society in these words:

The Jewish Palestine Exploration Society

It has finally happened. At the National Library in Jerusalem a society has been founded whose above-mentioned name attests to its nature, aims and goals.

This land is terra incognita to us, and we are supposed to acquire it not by force and not by might, but by the spirit. And where is that spirit that revives us? There is these days no nation capable of occupying a land by force alone; every land that a cultured nation (and only such a nation can conquer lands in our day and age) conquers and plans to hold, it must first thoroughly investigate.

A short time later, an announcement appeared on behalf of the Society to explain its purpose. It emerges that it sought, among other things, to close a certain gap that prevailed and to act as a substitute for an organized department of antiquities and a museum that did not exist under Ottoman rule. David Yellin was selected to head the committee, Abraham Jacob Brawer as its secretary, and its members included Aharon Meir Mazie, Eliezer Meir Lipschuetz, Avraham Baruch Rosenstein and Abraham Solomon Waldstein.

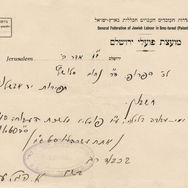

Unfortunately, no archival information remains from the Society’s early days. A letter written by Yellin and Brawer has been preserved, presenting the newly formed society to their German colleagues at the veteran Deutsche Palaestina Verein, founded in 1877.[2] This would appear to be the earliest document concerning the Jewish Palestine Exploration Society. Considerable information on the beginnings of the Society also appears in the articles by Brawer marking the Society’s 30th and 50th anniversaries.

Like every beginning, that of the Israel Exploration Society was fraught with difficulty. We know of no clear activity, certainly not activity involving the exploration of the Land of Israel and its antiquities. The founders should not be blamed as this was an unsettled period of Ottoman rule. The available resources were small and the administration was hostile to such activity. It should be recalled that only two years earlier in 1911 there had been a major scandal caused by the British explorer Montague B. Parker’s attempt to excavate in search of treasure at the Temple Mount. The Jewish reaction to this came in the form of Raymond Weill’s excavations at the City of David Hill in 1913–1914, an initiative of the Baron Rothschild who funded it.

Shortly after its foundation the Society ceased to function. Brawer blames this on the Language Dispute, which drew all of the public’s attention, followed by World War I.

Upon the creation of the British Mandate for Palestine in 1920, the hostile environment was replaced by one favorable to archaeological research and the Society was founded a second time (29 November 1919), or if one prefers, renewed its activity, this time in a more substantial fashion. The initiative for the re-establishment of the Society came from the same group of people, this time as the Hebrew (rather than “Jewish”) Palestine Exploration Society, apparently, according to Brawer, under the influence of Eliezar Ben-Yehuda, its deputy chairman. Unfortunately, we have no archival material concerning the foundation of the Society: neither for 1913 nor for 1920, however there is information in the archives of the Mandatory Department of Antiquities from the period following the Society’s re-establishment.

With the creation of the British Mandate, the Department of Antiquities of the Mandatory government was established under the direction of Prof. John Garstang. The basis for an effective and purposeful antiquities law was laid and a range of activities involving the study and preservation of the antiquities of Palestine began. Alongside the director of the Department of Antiquities, an Archaeological Advisory Board was created. The first meeting of the Advisory Board was held on 20 September 1920, with High Commissioner Herbert Samuel in attendance. The relevant administrative file in the Mandatory Department of Antiquities archive contains documents relating to the appointment of the members of this board during the years 1920–1924. Roughly half of the file deals with the representative of the Jewish community of Palestine. In the first document in the file, dated 19 August 1920, Ben-Yehuda announces, in French, that in consort with Menachem Ussishkin, president of the Commission Sioniste (Zionist Commission), Prof. Nahum Slouschz would be the representative of the Jewish Palestine Exploration Society on the Archaeological Advisory Board. However, a few days later on 24 August 1920 an official letter arrived from the Zionist Commission to the Department of Antiquities stating that Ben-Yehuda was mistaken. Neither Ussishkin nor the Zionist Commission had agreed to appoint Slouschz as representative on the Archaeological Advisory Board. The letter noted that they hope to receive the name of the representative from the Zionist Union in London and would submit it to the Department of Antiquities.

Participants at the first meeting of the Advisory Board included Garstang, director of the Department of Antiquities; W.J. Pythian Adams of the British School in Jerusalem; the architect Antonio Barluzzi; Father LeGrange of the Ecole Biblique in Jerusalem; Archimandite Kleophas, the Greek Orthodox patriarch of Jerusalem; and Dr. W.F. Albright, director of the American Schools of Oriental Research in Jerusalem. The Jewish representative was Arthur Ruppin. The high commissioner later intervened on this matter, expressing a preference for the presence of a scholar rather than a Zionist leader to represent the Yishuv. He notified the director of the Department of Antiquities that it had been understood that the representative would be Slouschz and not Ruppin. The relations prevailing between the Zionist Commission and the Jewish Palestine Exploration Society are not entirely clear, however on 18 August1921 the Zionist Commission requested a letter from the Department of Antiquities stating that the representative should be Jewish, with scientific skills in the field of archaeology, such as Weill, for example. They appear to have persisted in wanting one of their own kind as representative.

Topics on the agenda of the first meeting of the Advisory Board included exemption of several types of antiquities from the Antiquities Law; a proposal for cooperation with the Pro Jerusalem Society; a proposal for the rehabilitation of the ancient synagogue at Capernaum; and construction at Gethsemane and on Mt. Tabor.

The second meeting was held on 28 September 1920 and the third on 2 November 1920. Afterward, the frequency of meetings was reduced to 4–5 per year. Only in April 1921 did an Arab member, Ismail Bey al-Husseini, join the Advisory Board. The second half of the file described above deals mainly with problems of translating documents to Arabic for the Arab representative.

Prof. Nahum Slouschz’s excavations at Tiberias

By the third meeting of the Advisory Board representatives of the Jewish Palestine Exploration Society had begun archaeological activity throughout the country. Participating in the meeting were Slouschz as a permanent member (though he was replaced shortly after) and Ben-Yehuda.

The protocol of the meeting is instructive since it reflects several scientific goals (the background to some is not entirely clear). We read in the protocol[הלא1] :

[[insert original English text here]]

Slousch reported on his probes at Caesarea to the Advisory Board (we have no information concerning what these involved or where in Caesarea the work was carried out). Ben-Yehuda expressed the desire that his Society conduct probes at a site that he believed to be a Philistine city at Artuf (=Hartuv). He noted that the Society expected to receive assistance from the property owners. Ben-Yehuda noted that a Mr. XXX (a blank space was left here) would oversee this (once again, we have no information concerning what was involved).

Father LeGrange, representing the Ecole Biblique, requested that the task of excavating the ʿAyn Duq mosaic be reserved for the Ecole Biblique, since it appeared that the Jewish Palestine Exploration Society had already proposed two other tasks. It was understood that he had previously present a request to carry out this task. Ben-Yehuda and Slouschz cordially agreed to rescind their request for the site of ʿAyn Duq in favor of the Ecole Biblique.

It was agreed that the sites of Tiberias and Hartuv would be reserved for the Jewish Palestine Exploration Society. Simultaneously a license to conduct soundings was issued to the “Jewish Archaeological Society” and Slouschz was issued a license to conduct soundings at Tiberias from 2 November 1920 to 2 January1921, in order to determine if the site was appropriate for excavations. Thus, it was decided that the site of ʿAyn Duq would be kept for the Ecole Biblique. It appears that at that point the unofficial professional ethic prevailed that persists in Israel to this day, whereby an excavator or institution will not conduct an excavation at a site previously excavated by others without first receiving the latter’s permission.

On 5 April 1921 Slouschz made an oral report on his excavations to the Department of Antiquities, as attested in a memorandum of the interview with him. He reported the find of a row of columns, five standing in situ, mosaic pavements, Corinthian capitals, and a sarcophagus bearing Greek and Kufic inscriptions. This is the first report of the discovery of a synagogue at Hammat Tiberias. It is symbolic that in that excavation, the first carried out by any Jewish institution in the country, an ancient synagogue from the period of the Geonim, Tiberias’s heyday, was uncovered. Equally symbolic, the most important find in that excavation is a seven-branched menorah carved in stone relief, a unique find to this day with no known parallel. Thus, the core of the collection of antiquities took shape, housed for a time in the Mahanaim Building (today Building A of the Ministry of Education and Culture) in Jerusalem, under the curatorship of S. Raphaeli. This collection formed the core of the Bezalel Museum and eventually of the Israel Museum, Jerusalem.

On 6 April 1921 Garstang gave Yellin a check for £30, a contribution of the British School toward Slouschz’s excavations at Tiberias. Yellin replied with a letter of thanks. The reason for this generosity is not known.

There is information about another excavation, though unclear if it was actually conducted. On 26 November 1921 Slouschz was issued Permit no. VIII to excavate at Silwan in a field belonging to Dawood Suleiman between the Dung Gate and the Siloam Pool. Since the location noted is general, we know only that it would have been located somewhere on the City of David Hill or in the Tyropoeon Valley.

The Ophel Excavation Campaign

At the 16 November1922 Advisory Board meeting, Garstang presented the idea of conducting an excavation campaign on the Ophel Hill, which is part of the City of David. Ben-Yehuda represented the Society. I have written about this episode in some detail elsewhere. In brief: upon Garstang’s appointment as director of the Mandatory Department of Antiquities he immediately recognized the importance of the hill identified with the City of David. Since he attributed international importance to it, he initiated an international excavation campaign there. However, his appeals to a long list of archaeological institutions worldwide received only minor response. The pre-condition that each body excavating would guarantee funding in the amount of £5,000 was a further obstacle. In the end, only three organizations expressed a real readiness to take part: the British, the French and the Jews, through the Jewish Palestine Exploration Society. The British barely managed to raise the funds and also had difficulty recruiting an excavator (in the end R.A. Stewart Macalister agreed). The French enjoyed the generous funding of the Baron Rothschild, and the Jewish-French archaeologist Weill agreed to return to excavate. The Jewish Palestine Exploration Society received a license, and would probably have found someone to cover the cost, even though at first it reported that it had 1,000 Egyptian pounds for the project, but did not have the required amount and consequently did not participate in the excavation.

Replacement of the representative in the Advisory Board

At the 14 February 1923 meeting of the Advisory Board, which took place following the death of Ben-Yehuda, Yellin represented the Society, which then nominated Dr. Joseph Klausner for membership on the Advisory Board, however the high commissioner was opposed to the Jewish community having two representatives. Unlike the Jewish Palestine Exploration Society, which wanted Ben-Yehuda (and prior to that, Slouschz) as representatives on the Advisory Board, the British regarded them as representatives of the entire Jewish Yishuv rather than representatives of a specific organization. The Hebrew University had not yet been founded at that time and the activities of its archaeological researchers began only much later. Yellin informed the director that the Society had appointed Yeshayahu Press as its representative. Later, they informed Press that the high commissioner had already approached Klausner and begged his forgiveness for the error. At the following meeting on 9 July 1923, Yellin (by special invitation) and Klausner were both present, apparently in connection with the Ophel excavation campaign.

Over the course of three years Slouschz, Ruppin, Ben-Yehuda, Yellin, Klausner (and nearly, Press) attended meetings of the Advisory Board on behalf of the Jewish Yishuv or the Jewish Palestine Exploration Society. This is a clear indication of the tremendous interest on the part of the Jewish sector in investigation of the distant past. This becomes even more evident in an additional letter, marked “classified” found in the file, from the director of the Department of Antiquities to the general secretary of the Mandate government on the attendance record of the members of the Advisory Board at its meetings. That year (1923) four meetings were held: Barluzzi—0; Richmond (instead of the director Garstang, later to become the next director)—2; the metropolitan from Nazareth—0; Ismail Husseini—1; Klausner—4.

The following episode also pertains to those first years: On 24 December 1923, approximately a year after Ben-Yehuda’s death, the Faithful Trust in Memory of Eliezar Ben-Yehuda approached the Mandatory Department of Antiquities with a request to transfer an ancient column from the City of David and place it as a memorial on his tomb. They were informed that an organization of some sort must take responsibility for this and they request to be that body. The Advisory Board discussed this and decided in favor, however the plan appears not to have been carried out.

Excavation at Absalom’s Tomb

I conclude my examination of the relations between the Mandatory Department of Antiquities and the Jewish Palestine Exploration Society during its early years noting the Slouschz excavation at Absalom’s Tomb (1924). More accurately, this was more a clean-up of the bottom of the monument, removing earth that had accumulated around it over the ages and the exposure of the opening of the Cave of Jehoshaphat behind it. While a report about this was written, it includes only a few details and all are known. Thus, Nahman Avigad, who conducted comprehensive research of the monument, had little criticism of it.

A few seconds of Slouschz’s excavation were preserved for posterity, documented in a film by the cineaste Yaakov Ben-Dov, the father of Hebrew film in Palestine. Slouschz appears dressed in a suit, standing on the monument’s podium and a few laborers work to remove the obstructing earth. This would appear to be the first archaeological excavation in the Land of Israel to have been captured on film.

Summary

The above are episodes from the “second founding” of the Jewish Palestine Exploration Society, the first Jewish scholarly society whose members were concerned with researching the Land of Israel. In their desire to research the land directly by exposing its past from beneath the layers of earth that had covered it over the centuries, they represent another aspect of the intellectual circles active in Palestine in their day. In so doing these groups sought to be like all the nations (British, German, French and American) that established similar societies in the Holy Land in the second half of the 19th century and beginning of the 20th. Despite the failed initial founding of the Society in 1913, the second attempt in 1920 was successful.

Although none of the founders and those initially active were true archaeologists (Slouschz dealt with study of Phoenician script), or had any field experience, they appreciated the necessity of fieldwork and achieved credible results for their time. Their activity vis-à-vis the newly founded Department of Antiquities attest to the desire to act insofar as possible, despite their meager resources. These modest beginnings presaged a glorious future, beginning in 1936 with the discovery of the ancient Jewish necropolis at Beth Shearim and Benjamin Mazar’s excavations there. But that is a topic for a separate chapter.

[1] While the Society’s name in English remained Jewish Palestine Exploration Society, in its Hebrew name, “Jewish” was changed to “Hebrew” in 1920. Following the establishment of the State of Israel and at the behest of its first prime minister, David Ben-Gurion, “Hebrew” was dropped from the Society’s Hebrew name, “Jewish” was dropped from its English name, and “Palestine” was replaced by “Israel,” hence its present name.

[2] With thanks to my colleague Dr. Hanswulf Bloedhorn, who brought the existence of this document to my attention.

[הלא1]as this is a document of the Department of Antiquities in English—obtain the original text